Prehistory

Ksar Akil 10 km northeast of Beirut is a large rock shelter below a steep limestone cliff where excavations have shown occupational deposits reaching down to a depth of 23.6 metres (77 ft) with one of the longest sequences of Paleolithic flint industries ever found in the Middle East. The first level of 8 metres (26 ft) contained Upper Levalloiso-Mousterian remains with long and triangular Lithic flakes. The level above this showed industries accounting for all six stages of the Upper Paleolithic. An Emireh point was found at the first stage of this level (XXIV), at around 15.2 metres (50 ft) below datum with a complete skeleton of an eight-year-old Homo Sapiens (called Egbert, now in the National Museum of Beirut after being studied in America) was discovered at 11.6 metres (38 ft), cemented into breccia. A fragment of a Neanderthal maxilla was also discovered in material from level XXVI or XXV, at around 15 metres (49 ft). Studies by Hooijer showed Capra and Dama were dominant in the fauna along with Stephanorhinus in later Levalloiso-Mousterian levels.[1]

It is believed to be one of the earliest known sites containing Upper Paleolithic technologies. Artifacts recovered from the site include Ksar Akil flakes, the main type of tool found at the site, along with shells with holes and chipped edge modifications that are suggested to have been used as pendants or beads. These indicate that the inhabitants were among the first in Western Eurasia to use personal ornaments. Results from radiocarbon dating indicate that the early humans may have lived at the site approximately 45,000 years ago or earlier. The presence of personal ornaments at Ksar Akil is suggestive of modern human behavior. The findings of ornaments at the site are contemporaneous with ornaments found at Late Stone Age sites such as Enkapune ya muto.[2][3][4]

Ancient Near East

The earliest prehistoric cultures of Lebanon, such as the Qaraoun culture gave rise to the civilization of the Canaanite period, when the region was populated by ancient peoples, cultivating land and living in sophisticated societies during the 2nd millennium BC. Northern Canaanites are mentioned in the Bible as well as in other Semitic records from that period.

Canaanites were the creators of the oldest known 24-letter alphabet, a shortening of earlier 30-letter alphabets such as Proto-Sinaitic and Ugaritic. The Canaanite alphabet later developed into the Phoenician one (with sister alphabets of Hebrew, Aramaic and Moabite), influencing the entire Mediterranean region.

The coastal plain of Lebanon is the historic home of a string of coastal trading cities of Semitic culture, which the Greeks termed Phoenicia, whose maritime culture flourished there for more than 1000 years. Ancient ruins in Byblos, Berytus (Beirut), Sidon, Sarepta (Sarafand), and Tyre show a civilized nation, with urban centres and sophisticated arts. Phoenicia was a cosmopolitan centre for many nations and cultures.

Its people roamed the Mediterranean seas, skilled in trade and in art, and founded trading colonies. The ancient Phoenicians set sail and colonized overseas. Their most famous colonies were Cadiz in today’s Spain and Carthage in today’s Tunisia.

Phoenicia maintained an uneasy tributary relationship with the neo-Assyrian and neo-Babylonian empires during the 9th to 6th centuries BC.

Classical Antiquity

After the gradual decline of their strength, the Phoenician city-states on the Lebanese coast were conquered outright in 539 BCE by Achaemenid Persia under Cyrus the Great,[5] who organized it as a satrapy (though many Phoenician colonies continued their independent existence – most notably Carthage.) The Persians forced some of the population to migrate to Carthage, which remained a powerful nation until the Second Punic War.[5] After two centuries of Persian rule, the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great, during his war against Persia, attacked and burned Tyre, the most prominent Phoenician city. He conquered what is now Lebanon and other nearby regions in 332 BCE.[5] After Alexander’s death the region was absorbed into the Seleucid Empire.

Christianity was introduced to the coastal plain of Lebanon from neighboring Galilee, already in the 1st century. The region, as with the rest of Syria and much of Anatolia, became a major center of Christianity. In the 4th century it was incorporated into the Christian Byzantine Empire. Mount Lebanon and its coastal plain became part of the Diocese of the East, divided to provinces of Phoenice Paralia and Phoenice Libanensis (which also extended over large parts of modern Syria).

During the late 4th and early 5th century, a hermit named Maron established a monastic tradition, focused on the importance of monotheism and asceticism, near the mountain range of Mount Lebanon. The monks who followed Maron spread his teachings among the native Lebanese Christians and remaining pagans in the mountains and coast of Lebanon. These Lebanese Christians came to be known as Maronites, and moved into the mountains to avoid religious persecution by Roman authorities.[6] During the frequent Roman-Persian Wars that lasted for many centuries, the Sassanid Persians occupied what is now Lebanon from 619 to 629.[7]

Middle Ages

Arab rule

During the 7th century AD the Muslim Arabs conquered Syria soon after the death of Muḥammad, establishing a new regime to replace the Romans (or Byzantines as the Eastern Romans are sometimes called). Though Islam and the Arabic language were officially dominant under this new regime, the general populace still took time to convert from Christianity and the Syriac language. In particular, the Maronite community clung to its faith and managed to maintain a large degree of autonomy despite the succession of rulers over Syria. Muslim influence increased greatly in the seventh century, when the Umayyad capital was established at nearby Damascus.

During the 11th century the Druze faith emerged from a branch of Islam. The new faith gained followers in the southern portion of Lebanon. The Maronites and the Druze divided Lebanon until the modern era. The major cities on the coast, Acre, Beirut, and others, were directly administered by Muslim Caliphs. As a result, the people became increasingly absorbed by Arabic culture.

Crusader kingdoms

Following the fall of Roman/Christian Anatolia to the Muslim Turks, the Romans put out a call to the Pope in Rome for assistance in the 11th century. The result was a series of wars known as the Crusades launched by Latin Christians (of mainly French origin) in Western Europe to reclaim the former Roman territories in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially Syria and Palestine (the Levant). Lebanon was in the main path of the First Crusade‘s advance on Jerusalem. Frankish nobles occupied areas within present-day Lebanon as part of the southeastern Crusader States. The southern half of present-day Lebanon formed the northern march of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; the northern half was the heartland of the County of Tripoli. Although Saladin eliminated Christian control of the Holy Land around 1190, the Crusader states in Lebanon and Syria were better defended.

One of the most lasting effects of the Crusades in this region was the contact between the crusaders (mainly French) and the Maronites. Unlike most other Christian communities in the region, who swore allegiance to Constantinople or other local patriarchs, the Maronites proclaimed allegiance to the Pope in Rome. As such the Franks saw them as Roman Catholic brethren. These initial contacts led to centuries of support for the Maronites from France and Italy, even after the later fall of the Crusader states in the region.

Mamluk rule

Muslim control of Lebanon was reestablished in the late 13th century under the Mamluk sultans of Egypt. Lebanon was later contested between Muslim rulers until the Turkish Ottoman Empire solidified authority over the eastern Mediterranean.

Ottoman control was uncontested during the early modern period, but the Lebanese coast became important for its contacts and trades with Venice and other Italian city-states.

The mountainous territory of Mount Lebanon has long been a shelter for minority and persecuted groups, including its historic Maronite Christian majority and Druze communities. It was an autonomous region of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman rule

Starting from the 13th century, the Ottoman Turks formed an empire which came to encompass the Balkans, Middle East and North Africa. The Ottoman sultan Selim I (1516–20), after defeating the Persians, conquered the Mamluks. His troops, invading Syria, destroyed Mamluk resistance in 1516 at Marj Dabaq, north of Aleppo.[8]

During the conflict between the Mamluks and the Ottomans, the amirs of Lebanon linked their fate to that of Ghazali, governor (pasha) of Damascus. He won the confidence of the Ottomans by fighting on their side at Marj Dabaq and, apparently pleased with the behavior of the Lebanese amirs, introduced them to Salim I when he entered Damascus. Salim I, whose treasury was depleted by the wars, decided to grant the Lebanese amirs a semiautonomous status in exchange for their acting as “tax farmers”. The Ottomans, through the two main feudal families, the Maans who were Druze and the Chehabs who were Sunni Muslim Arab converts to Maronite Christianity, ruled Lebanon until the middle of the nineteenth century. During Ottoman rule the term Syria was used to designate the approximate area including present-day Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine.[8]

The Maans, 1120-1697

The Maans came to Lebanon from Yemen sometime in the 11th or 12th centuries. They were a tribe and dynasty of Qahtani Arabs who settled on the southwestern slopes of the Lebanon Mountains and soon adopted the Druze religion. Their authority began to rise with Fakhr ad-Din I, who was permitted by Ottoman authorities to organize his own army, and reached its peak with Fakhr ad-Din II (1570–1635). (The existence of “Fakhr ad-Din I” has been questioned by some scholars.)[8][9]

Fakhreddine II

Born in Baakline to a Druze family, his father died when he was 13, and his mother entrusted her son to another princely family, probably the Khazens (al-Khazin). In 1608 Fakhr-al-Din forged an alliance with the Italian Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The alliance contained both a public economic section and a secret military one. Fakhr-al-Din’s ambitions, popularity and unauthorized foreign contacts alarmed the Ottomans who authorized Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, Muhafiz of Damascus, to mount an attack on Lebanon in 1613 in order to reduce Fakhr-al-Din’s growing power. Professor Abu-Husayn has made the Ottoman archives relevant to the emir’s career available. Faced with Hafiz’s army of 50,000 men, Fakhr-al-Din chose exile in Tuscany, leaving affairs in the hands of his brother Emir Yunis and his son Emir Ali Beg. They succeeded in maintining most of the forts such as Banias (Subayba) and Niha which were a mainstay of Fakhr ad-Din’s power. Before leaving, Fakhr ad-Din paid his standing army of soqbans (mercenaries) two years wages in order to secure their loyalty. Hosted in Tuscany by the Medici Family, Fakhr-al-Din was welcomed by the grand duke Cosimo II, who was his host and sponsor for the two years he spent at the court of the Medici. He spent a further three years as guest of the Spanish Viceroy of Sicily and then Naples, the Duke Osuna. Fakhr-al-Din had wished to enlist Tuscan or other European assistance in a “Crusade” to free his homeland from Ottoman domination, but was met with a refusal as Tuscany was unable to afford such an expedition. The prince eventually gave up the idea, realizing that Europe was more interested in trade with the Ottomans than in taking back the Holy Land. His stay nevertheless allowed him to witness Europe’s cultural revival in the 17th century, and bring back some Renaissance ideas and architectural features. By 1618, political changes in the Ottoman sultanate had resulted in the removal of many of Fakhr-al-Din’s enemies from power, allowing Fahkr-al-Din’s return to Lebanon, whereupon he was able quickly to reunite all the lands of Lebanon beyond the boundaries of its mountains; and having revenge from Emir Yusuf Pasha ibn Siyfa, attacking his stronghold in Akkar, destroying his palaces and taking control of his lands, and regaining the territories he had to give up in 1613 in Sidon, Tripoli, Bekaa among others. Under his rule, printing presses were introduced and Jesuit priests and Catholic nuns encouraged to open schools throughout the land.

In 1623, the prince angered the Ottomans by refusing to allow an army on its way back from the Persian front to winter in the Bekaa. This (and instigation by the powerful Janissary garrison in Damascus) led Mustafa Pasha, Governor of Damascus, to launch an attack against him, resulting in the battle at Majdel Anjar where Fakhr-al-Din’s forces although outnumbered managed to capture the Pasha and secure the Lebanese prince and his allies a much needed military victory. The best source (in Arabic) for Fakhr ad-Din’s career up to this point is a memoir signed by al-Khalidi as-Safadi, who was not with the Emir in Europe but had access to someone who was, possibly Fakhr ad-Din himself. However, as time passed, the Ottomans grew increasingly uncomfortable with the prince’s increasing powers and extended relations with Europe. In 1632, Kuchuk Ahmed Pasha was named Muhafiz of Damascus, being a rival of Fakhr-al-Din and a friend of Sultan Murad IV, who ordered Kuchuk Ahmed Pasha and the sultanate’s navy to attack Lebanon and depose Fakhr-al-Din.

This time, the prince had decided to remain in Lebanon and resist the offensive, but the death of his son Emir Ali Beik in Wadi el-Taym was the beginning of his defeat. He later took refuge in Jezzine’s grotto, closely followed by Kuchuk Ahmed Pasha. He surrendered to the Ottoman general Jaafar Pasha, whom he knew well, under circumstances that are not clear. Fakhr-al-Din was taken to Constantinople and kept in the Yedikule (Seven Towers) prison for two years. He was then summoned before the sultan. Fakhr-al-Din, and one or two of his sons, were accused of treason and executed there on 13 April 1635. There are unsubstantiated rumors that the younger of the two boys was spared and raised in the harem, later becoming Ottoman ambassador to India.

Although Fakhr ad-Din II’s aspirations toward complete independence for Lebanon ended tragically, he greatly enhanced Lebanon’s military and economic development. Noted for religious tolerance, the Druze prince attempted to merge the country’s different religious groups into one Lebanese community. In an effort to attain complete independence for Lebanon, he concluded a secret agreement with Ferdinand I, grand duke of Tuscany. Following his return from Tuscany, Fakhr ad-Din II, realizing the need for a strong and disciplined armed force, channeled his financial resources into building a regular army. This army proved itself in 1623, when Mustafa Pasha, the new governor of Damascus, underestimating the capabilities of the Lebanese army, engaged it in battle and was decisively defeated at Anjar in the Biqa Valley.[8]

In addition to building up the army, Fakhr ad-Din II, who became acquainted with Italian culture during his stay in Tuscany, initiated measures to modernize the country. After forming close ties and establishing diplomatic relations with Tuscany, he brought in architects, irrigation engineers, and agricultural experts from Italy in an effort to promote prosperity in the country. He also strengthened Lebanon’s strategic position by expanding its territory, building forts as far away as Palmyra in Syria, and gaining control of Palestine. Finally, the Ottoman sultan Murad IV of Istanbul, wanting to thwart Lebanon’s progress toward complete independence, ordered Kutshuk, then governor of Damascus, to attack the Lebanese ruler. This time Fakhr ad-Din was defeated, and he was executed in Istanbul in 1635. No significant Maan rulers succeeded Fakhr ad-Din II.[8]

Fakhreddine is regarded by the Lebanese as the best leader and prince the country has ever seen. The Druze prince treated all the religions equally and was the one who formed Lebanon. Lebanon has achieved during Fakhreddine’s reign enormous heights that the country had and would never witness again.

The Shihabs, 1697-1842

The Shihabs succeeded the Maans in 1697 after the Battle of Ain Dara, a battle that changed the face of Lebanon back then, where a clash between two Druze clans broke up: the Qaysis and the Yemenis. The Druze Qaysis, led back then by Ahmad Shihab, won and expelled the Yemenis from Lebanon to Syria. This has led to an enormous decrease to the Druze population in Mount-Lebanon, who were a majority back then and helped the Christians overcome the Druze demographically. This Qaysi ‘victory’ gave the Shihab, who were Qaysis themselves and the allies of Lebanon, the rule over Mount-Lebanon. The Druze overlords voted for the Shihabs to rule Mount Lebanon and the Chouf by the threat of the Ottoman Empire who wanted the Sunnis to rule Lebanon. The Shihabs originally lived in the Hawran region of southwestern Syria and settled in Wadi al-Taym in southern Lebanon. The most prominent among them was Bashir Shihab II. His ability as a statesman was first tested in 1799, when Napoleon besieged Acre, a well-fortified coastal city in Palestine, about forty kilometers south of Tyre. Both Napoleon and Al Jazzar, the governor of Acre, requested assistance from the Shihab leader; Bashir, however, remained neutral, declining to assist either combatant. Unable to conquer Acre, Napoleon returned to Egypt, and the death of Al Jazzar in 1804 removed Bashir’s principal opponent in the area. The Shihabs were originally a Sunni Muslim family, but had converted to Christianity.[8]

The rise and fall of Emir Bashir II

In 1788 Bashir Shihab II (sometimes spelled Bachir in French sources) would rise to become the Emir. Born into poverty, he was elected emir upon the abdication of his predecessor, and would rule under Ottoman suzerainty, being appointed wali or governor of Mt Lebanon, the Biqa valley and Jabal Amil. Together this is about two thirds of modern-day Lebanon. He would reform taxes and attempt to break the feudal system, in order to undercut rivals, the most important of which was also named Bashir: Bashir Jumblatt, whose wealth and feudal backers equaled or exceeded Bashir II – and who had increasing support in the Druze community. In 1822 the Ottoman wali of Damascus went to war with Acre, which was allied with Muhammad Ali, the pasha of Egypt. As part of this conflict one of the most remembered massacres of Maronite Christians by Druze forces occurred, forces that were aligned with the wali of Damascus. Jumblatt represented the increasingly disaffected Druze, who were both shut out from official power and angered at the growing ties with the Maronites by Bashir II, who was himself a Maronite Christian.

Bashir II was overthrown as wali when he backed Acre, and fled to Egypt, later to return and organize an army. Jumblatt gathered the Druze factions together, and the war became sectarian in character: the Maronites backing Bashir II, the Druze backing Bashir Jumblatt. Jumblatt declared a rebellion, and between 1821 and 1825 there were massacres and battles, with the Maronites attempting to gain control of the Mt. Lebanon district, and the Druze gaining control over the Biqa valley. In 1825 Bashir II, helped by the Ottomans and the Jezzar, defeated his rival in the Battle of Simqanieh. Bashir Jumblatt died in Acre at the order of the Jezzar. Bashir II was not a forgiving man and repressed the Druze rebellion, particularly in and around Beirut. This made Bashir Chehab the only leader of Mount-Lebanon. However, Bashir Chehab was depicted as a nasty leader because Bashir Jumblatt was his all-time friend and has saved his life when the Keserwan peasants tried to kill the prince, by sending 1000 of his men to save him. Also, days before the Battle of Simqania, Bashir Jumblatt had the chance to kill Bashir II when he was returning from Acre when he reportedly kissed the Jezzar’s feet in order to help him against Jumblatt, but Bashir II reminded him of their friendship and told Jumblatt to “pardon when you can”. The high morals of Jumblatt led him to pardon Bashir II, a decision he should have regretted.

Bashir II, who had come to power through local politics and nearly fallen from power because of his increasing detachment from them, reached out for allies, allies who looked on the entire area as “the Orient” and who could provide trade, weapons and money, without requiring fealty and without, it seemed, being drawn into endless internal squabbles. He disarmed the Druze and allied with France, governing in the name of the Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali, who entered Lebanon and formally took overlordship in 1832. For the remaining 8 years, the sectarian and feudal rifts of the 1821–1825 conflict were heightened by the increasing economic isolation of the Druze, and the increasing wealth of the Maronites.

During the nineteenth century the town of Beirut became the most important port of the region, supplanting Acre further to the south. This was mostly because Mount Lebanon became a centre of silk production for export to Europe. This industry made the region wealthy, but also dependent on links to Europe. Since most of the silk went to Marseille, the French began to have a great impact in the region.

Sectarian conflict: European Powers begin to intervene

The discontent grew to open rebellion, fed by both Ottoman and British money and support: Bashir II fled, the Ottoman Empire reasserted control and Mehmed Hüsrev Pasha, whose sole term as Grand Vizier ran from 1839 to 1841, appointed another member of the Shihab family, who styled himself Bashir III. Bashir III, coming on the heels of a man who by guile, force and diplomacy had dominated Mt Lebanon and the Biqa for 52 years, did not last long. In 1841 conflicts between the impoverished Druze and the Maronite Christians exploded: There was a massacre of Christians by the Druze at Deir al Qamar, and the fleeing survivors were slaughtered by Ottoman regulars. The Ottomans attempted to create peace by dividing Mt Lebanon into a Christian district and a Druze district, but this would merely create geographic powerbases for the warring parties, and it plunged the region back into civil conflict which included not only the sectarian warfare but a Maronite revolt against the Feudal class, which ended in 1858 with the overthrow of the old feudal system of taxes and levies. The situation was unstable: the Maronites lived in the large towns, but these were often surrounded by Druze villages living as perioikoi.

In 1860, this would boil back into full scale sectarian war, when the Maronites began openly opposing the power of the Ottoman Empire. Another destabilizing factor was France’s support for the Maronite Christians against the Druze which in turn led the British to back the Druze, exacerbating religious and economic tensions between the two communities. The Druze took advantage of this and began burning Maronite villages. The Druze had grown increasingly resentful of the favoring of the Maronites by Bashir II, and were backed by the Ottoman Empire and the wali of Damascus in an attempt to gain greater control over Lebanon; the Maronites were backed by the French, out of both economic and political expediency. The Druze began a military campaign that included the burning of villages and massacres, while Maronite irregulars retaliated with attacks of their own. However, the Maronites were gradually pushed into a few strongholds and were on the verge of military defeat when the Concert of Europe intervened[10] and established a commission to determine the outcome.[11] The French forces deployed there were then used to enforce the final decision. The French accepted the Druze as having established control and the Maronites were reduced to a semi-autonomous region around Mt Lebanon, without even direct control over Beirut itself. The Province of Lebanon that would be controlled by the Maronites, but the entire area was placed under direct rule of the governor of Damascus, and carefully watched by the Ottoman Empire.

The long siege of Deir al Qamar found a Maronite garrison holding out against Druze forces backed by Ottoman soldiers; the area in every direction was despoiled by the besiegers. In July 1860, with European intervention threatening, the Turkish government tried to quiet the strife, but Napoleon III of France sent 7,000 troops to Beirut and helped impose a partition: The Druze control of the territory was recognized as the fact on the ground, and the Maronites were forced into an enclave, arrangements ratified by the Concert of Europe in 1861. They were confined to a mountainous district, cut off from both the Biqa and Beirut, and faced with the prospect of ever-growing poverty. Resentments and fears would brood, ones which would resurface in the coming decades.

Youssef Bey Karam, a Lebanese nationalist played an influential role in Lebanon’s independence during this era.

Rising prosperity and peace

The remainder of the 19th century saw a relative period of stability, as Muslim, Druze and Maronite groups focused on economic and cultural development which saw the founding of the American University of Beirut and a flowering of literary and political activity associated with the attempts to liberalize the Ottoman Empire. Late in the century there was a short Druze uprising over the extremely harsh government and high taxation rates, but there was far less of the violence that had scalded the area earlier in the century.

In the approach to World War I, Beirut became a center of various reforming movements, and would send delegates to the Arab Syrian conference and Franco-Syrian conference held in Paris. There was a complex array of solutions, from pan-Arab nationalism, to separatism for Beirut, and several status quo movements that sought stability and reform within the context of Ottoman government. The Young Turk revolution brought these movements to the front, hoping that the reform of Ottoman Empire would lead to broader reforms. The outbreak of hostilities changed this, as Lebanon was to feel the weight of the conflict in the Middle East more heavily than most other areas occupied by the Syrians.

League of Nations Mandate

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the League of Nations mandated the five provinces that make up present-day Lebanon to the direct control of France. Initially the division of the Arabic-speaking areas of the Ottoman Empire were to be divided by the Sykes-Picot Agreement; however, the final disposition was at the San Remo conference of 1920, whose determinations on the mandates, their boundaries, purposes and organization was ratified by the League in 1921 and put into effect in 1922.

According to the agreements reached at San Remo, France had its control over what was termed Syria recognised, the French having taken Damascus in 1920. Like all formerly Ottoman areas, Syria was a Class A Mandate, deemed to “… have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory.” The entire French mandate area was termed “Syria” at the time, including the administrative districts along the Mediterranean coast. Wanting to maximize the area under its direct control, contain an Arab Syria centered on Damascus, and insure a defensible border, France moved the Lebanon-Syrian border to the Anti-Lebanon mountains, east of the Beqaa Valley, territory which had historically belonged to the province of Damascus for hundreds of years, and was far more attached to Damascus than Beirut by culture and influence. This doubled the territory under the control of Beirut, at the expense of what would become the state of Syria.

On October 27, 1919, the Lebanese delegation led by Maronite Patriarch Elias Peter Hoayek presented the Lebanese aspirations in a memorandum to the Paris Peace Conference. This included a significant extension of the frontiers of the Lebanon Mutasarrifate,[14] arguing that the additional areas constituted natural parts of Lebanon, despite the fact that the Christian community would not be a clear majority in such an enlarged state.[14] The quest for the annexation of agricultural lands in the Bekaa and Akkar was fueled by existential fears following the death of nearly half of the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate population in the Great Famine; the Maronite church and the secular leaders sought a state that could better provide for its people.[15] The areas to be added to the Mutasarrifate included the coastal towns of Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon and Tyre and their respective hinterlands, all of which belonged to the Beirut Vilayet, together with four Kazas of the Syria Vilayet (Baalbek, the Bekaa, Rashaya and Hasbaya).[14]

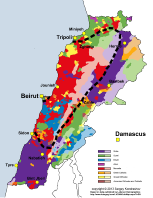

As a consequence of this also, the demographics of Lebanon were profoundly altered, as the added territory contained people who were predominantly Muslim or Druze: Lebanese Christians, of which the Maronites were the largest subgrouping, now constituted barely more than 50% of the population, while Sunni Muslims in Lebanon saw their numbers increase eightfold, and the Shi’ite Muslims fourfold. The Modern Lebanon’s constitution, drawn up in 1926, specified a balance of power between the various religious groups, but France designed it to guarantee the political dominance of its Christian allies. The president was required to be a Christian (in practice, a Maronite), the prime minister a Sunni Muslim. On the basis of the 1932 census, parliament seats were divided according to a six-to-five Christian/Muslim ratio. The constitution gave the president veto power over any legislation approved by parliament, virtually ensuring that the 6:5 ratio would not be revised in the event that the population distribution changed. By 1960, Muslims were thought to constitute a majority of the population, which contributed to Muslim unrest regarding the political system.

During World War II when the Vichy government assumed power over French territory in 1940, General Henri Fernand Dentz was appointed as high commissioner of Lebanon. This new turning point led to the resignation of Lebanese president Emile Edde on April 4, 1941. After 5 days, Dentz appointed Alfred Naccache for a presidency period that lasted only 3 months. The Vichy authorities allowed Nazi Germany to move aircraft and supplies through Syria to Iraq where they were used against British forces. Britain, fearing that Nazi Germany would gain full control of Lebanon and Syria by pressure on the weak Vichy government, sent its army into Syria and Lebanon.

After the fighting ended in Lebanon, General Charles de Gaulle visited the area. Under various political pressures from both inside and outside Lebanon, de Gaulle decided to recognize the independence of Lebanon. On November 26, 1941, General Georges Catroux announced that Lebanon would become independent under the authority of the Free French government.

Elections were held in 1943 and on November 8, 1943 the new Lebanese government unilaterally abolished the mandate. The French reacted by throwing the new government into prison. In the face of international pressure, the French released the government officials on November 22, 1943 and accepted the independence of Lebanon.

Republic of Lebanon

Independence and following years

The allies kept the region under control until the end of World War II. The last French troops withdrew in 1946.

Lebanon’s history from independence has been marked by alternating periods of political stability and turmoil interspersed with prosperity built on Beirut‘s position as a freely trading regional center for finance and trade. Beirut became a prime location for institutions of international commerce and finance, as well as wealthy tourists, and enjoyed a reputation as the “Paris of the Middle East” until the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War.

In the aftermath of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Lebanon became home to more than 110,000 Palestinian refugees.

Economic prosperity and growing tensions

In 1958, during the last months of President Camille Chamoun‘s term, an insurrection broke out, and 5,000 United States Marines were briefly dispatched to Beirut on July 15 in response to an appeal by the government. After the crisis, a new government was formed, led by the popular former general Fuad Chehab.

During the 1960s, Lebanon enjoyed a period of relative calm, with Beirut-focused tourism and banking sector-driven prosperity. Lebanon reached the peak of its economic success in the mid-1960s – the country was seen as a bastion of economic strength by the oil-rich Persian Gulf Arab states, whose funds made Lebanon one of the world’s fastest growing economies. This period of economic stability and prosperity was brought to an abrupt halt with the collapse of Yousef Beidas‘ Intra Bank, the country’s largest bank and financial backbone, in 1966.

Additional Palestinian refugees arrived after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Following their defeat in the Jordanian civil war, thousands of Palestinian militiamen regrouped in Lebanon, led by Yasser Arafat‘s Palestine Liberation Organization, with the intention of replicating the modus operandi of attacking Israel from a politically and militarily weak neighbour. Starting in 1968, Palestinian militants of various affiliations began to use southern Lebanon as a launching pad for attacks on Israel. Two of these attacks led to a watershed event in Lebanon’s inchoate civil war. In July 1968, a faction of George Habash‘s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked an Israeli El Al civilian plane en route to Algiers; in December, two PFLP gunmen shot at an El Al plane in Athens, resulting in the death of an Israeli.

As a result, two days later, an Israeli commando flew into Beirut’s international airport and destroyed more than a dozen civilian airliners belonging to various Arab carriers. Israel defended its actions by informing the Lebanese government that it was responsible for encouraging the PFLP. The retaliation, which was intended to encourage a Lebanese government crackdown on Palestinian militants, instead polarized Lebanese society on the Palestinian question, deepening the divide between pro- and anti-Palestinian factions, with the Muslims leading the former grouping and Maronites primarily constituting the latter. This dispute reflected increasing tensions between Christian and Muslim communities over the distribution of political power, and would ultimately foment the outbreak of civil war in 1975.

In the interim, while armed Lebanese forces under the Maronite-controlled government sparred with Palestinian fighters, Egyptian leader Gamal Abd al-Nasser helped to negotiate the 1969 “Cairo Agreement” between Arafat and the Lebanese government, which granted the PLO autonomy over Palestinian refugee camps and access routes to northern Israel in return for PLO recognition of Lebanese sovereignty. The agreement incited Maronite frustration over what were perceived as excessive concessions to the Palestinians, and pro-Maronite paramilitary groups were subsequently formed to fill the vacuum left by government forces, which were now required to leave the Palestinians alone. Notably, the Phalange, a Maronite militia, rose to prominence around this time, led by members of the Gemayel family.[16]

In September 1970 Suleiman Franjieh, who had left the country briefly for Latakia in the 1950s after being accused of killing hundreds of people including other Maronites, was elected president by a very narrow vote in parliament. In November, his personal friend Hafiz al-Asad, who had received him during his exile, seized power in Syria. Later, in 1976, Franjieh would invite the Syrians into Lebanon.[17]

For its part, the PLO used its new privileges to establish an effective “mini-state” in southern Lebanon, and to ramp up its attacks on settlements in northern Israel. Compounding matters, Lebanon received an influx of armed Palestinian militants, including Arafat and his Fatah movement, fleeing the 1970 Jordanian crackdown. The PLO’s “vicious terrorist attacks in Israel”[18] dating from this period were countered by Israeli bombing raids in southern Lebanon, where “150 or more towns and villages…have been repeatedly savaged by the Israeli armed forces since 1968,” of which the village of Khiyam is probably the best-known example.[19] Palestinian attacks claimed 106 lives in northern Israel from 1967, according to official IDF statistics, while the Lebanese army had recorded “1.4 Israeli violations of Lebanese territory per day from 1968–74”[20] Where Lebanon had no conflict with Israel during the period 1949–1968, after 1968 Lebanon’s southern border began to experience an escalating cycle of attack and retaliation, leading to the chaos of the civil war, foreign invasions and international intervention. The consequences of the PLO’s arrival in Lebanon continue to this day.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Lebanon

World Lebanese Cultural Union

World Lebanese Cultural Union